Dialogue with Alexandre Gilbert on the Hallelujah Effect and the Empedocles Effect*

First published in September of 2017, reblogged a month later, updated in memory of my friend and colleague, Stephen Freedman, who died suddenly at his home, 2 July 2018.

*This Dialogue was originally posted, thanks to Alexandre Gilbert, on The Times of Israelblog, 30 September 2017, featuring all four parts. For reading's sake, these questions are reblogged here, in this case, featuring the penultimate question Alexandre asks on the great Leonard Cohen – and the 'Hallelujah Effect.'

AG ::

3.

Lana del Rey, who studied Metaphysics at Fordham University attends an hommage

concert to Leonard Cohen in a few days, in Quebec. What is the Hallelujah

Effect you compared to the Empedocles Effect (Gaston Bachelard’s concept in

Psychoanalysis of Fire)?

BB ::

I wish this concert were

in NY!

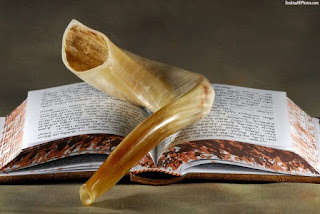

When you first wrote to me, on the sabbath of Yom Kippur in the days of awe as you frame your question, I found myself as astonished as ever by the wonder of Cohen who, as the Germans say, trägt seinen Namen zu recht: a priest for all of us.

Anyone in doubt of this might listen to this song written at the end of his life, and released scarcely a month before his death before Cohen’s death 7 November 2016: You want it darker.

When you first wrote to me, on the sabbath of Yom Kippur in the days of awe as you frame your question, I found myself as astonished as ever by the wonder of Cohen who, as the Germans say, trägt seinen Namen zu recht: a priest for all of us.

Anyone in doubt of this might listen to this song written at the end of his life, and released scarcely a month before his death before Cohen’s death 7 November 2016: You want it darker.

Stephen Freedman, Provost of Fordham

University — and, like Cohen himself, a native of Montreal — told me that Cohen’s congregation there had spent some time with that very song, again the link: You want it Darker. Recently, I have written further about the aptness and stark beauty, complexity and poetic suffering without complaint in this song in a coda appended to an essay on music and phenomenology, and very much about Cohen.

But that song, for all its beauty, and such dark reflections, do not constitute the ‘Hallelujah Effect.’

But that song, for all its beauty, and such dark reflections, do not constitute the ‘Hallelujah Effect.’

The ‘Hallelujah Effect’

is the power of song as a song deliberately composed, orchestrated, calculated to

work on us — what Rolling Stone (foremost perhaps among many others) describes as a mix of sex and religion. The focus is on erotic power,

obscurity and desire, including and not less the very same male-female dynamic

of sex and love, affirmation and shattering, that is also the reason I pay

attention to k.d lang, even when everyone tells me, sometimes unbidden, that

they prefer not even Cohen’s own version or John Cale’s orchestration, say, but

Jeff Buckley, an almost universal favorite or Rufus Wainwright.

Thus any talk of k.d. lang is a ringer and most of us, quite in spite of the over-suffusion of Hallelujah covers in our culture, return again and again, to a certain favorite, which favouring or ‘liking’ is a direct result of programming.

Thus any talk of k.d. lang is a ringer and most of us, quite in spite of the over-suffusion of Hallelujah covers in our culture, return again and again, to a certain favorite, which favouring or ‘liking’ is a direct result of programming.

The ‘Hallelujah

Effect’ is effected, deliberate, this

is where Adorno matters even more than Nietzsche, although Adorno also learns

from Nietzsche, via the constant repetition and plugging of specific songs what

H. Stith Bennett the sociologist of rock music calls ‘recording consciousness,’

where what our minds know more than the song is the very precise or exact sound

of a specific track: this, the effect of market branding or priming, is your

brain on Hallelujah.

The ‘Hallelujah

Effect’ is effected, deliberate, this

is where Adorno matters even more than Nietzsche, although Adorno also learns

from Nietzsche, via the constant repetition and plugging of specific songs what

H. Stith Bennett the sociologist of rock music calls ‘recording consciousness,’

where what our minds know more than the song is the very precise or exact sound

of a specific track: this, the effect of market branding or priming, is your

brain on Hallelujah.I love your allusion to Gaston Bachelard’s ‘Psychology of Fire’! Yet I would also say that Hölderlin’s poem Empedokles captures the allure and heroic danger of the ‘Empedocles effect.’

Perhaps as one can imagine this might have struck Cohen himself, as Empedocles chronicles the succession of love and strife, of lover’s quarrels as these echo the raging and waning of desire, to use Cohen’s final word, like Sophocles, on desire: the wretched beast is tame.

A poet like Cohen, Hölderlin

wrote of Empedocles — this is also the ‘Empedocles effect’ — :

Life

you sought, seeking, and welling up and gleaming

from

the depths of earth, for you a divine fire,

And

you, aquiver with desire,

Hurl

yourself down into Aetna’s flames.

Thus what Cohen calls ‘the

holy and the broken Hallelujah’ echoes one of the oldest poetic dreams of ancient

Greece.

This is the lover’s idea of dancing on the volcano, dancing, for Cohen, ‘to the end of love,’ including the naked consequences of what it is to be, like Hölderlin, like Cohen, ‘head-drenched in fire.’

This is the lover’s idea of dancing on the volcano, dancing, for Cohen, ‘to the end of love,’ including the naked consequences of what it is to be, like Hölderlin, like Cohen, ‘head-drenched in fire.’

I read it that way but media

moguls have other ideas and from the beginning of the book Adorno called the ‘current

of music,’ the ‘radio effect’ — i.e., your brain on YouTube — hijacks your

consciousness, brands you with one song, and sends you in a spin of both

attention and disinterest. That

branding, that mind-hack, is the ‘Hallelujah

Effect,’ and it’s all around us, no need to read Hölderlin’s poetry or Cohen’s

poetry or any other kind of poetry.

Comments

Post a Comment